As we’ve covered previously, 2014 was a solid year for documentary filmmaking, and this raises a question…

… are you going to be part of 2015’s legacy?

Whether you’re still grafting at documentary filmmaking school or already qualified and shooting out in the field, it’s never a bad idea to take pause and reflect on some of the best practices of crafting a documentary (while you work on innovating and finding your own ‘voice’.)

No matter what level of experience you may currently find yourself, let’s revisit what’s at the very core of our artform:

1. The Golden Rule: There Are No Rules

It sounds corny, but there really isn’t a blanket tip that will bring the best out of every documentary. If there’s one single thing that should be kept in mind, it’s that every story will require different telling techniques: you’ll have to rummage through your cinematography toolbox and figure out which tool is right for the job, and that kind of intuition (as well as acquiring the tools in the first place) only comes through practice.

Another thing to keep in mind is that no amount of practice or experience will ever see you knowing it all, so with that in mind…

2. Surround Yourself With Talent

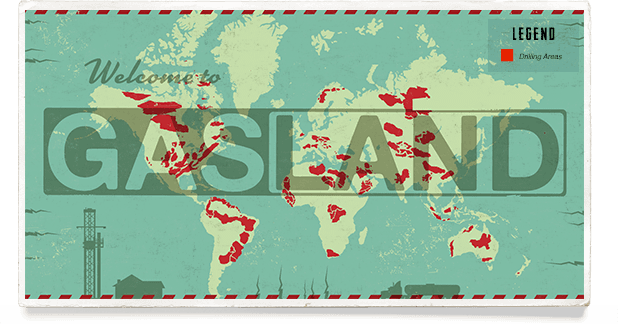

We can think of very few documentaries that are written, directed, shot and produced by a single-person film crew. In fact, Gasland is the only critically notable example that springs to mind, and even that ended up having a few people working on it by the end of production.

We’re not saying it’s impossible to go it solo, but unless you’ve got absolutely no other option, it’s not going to be an easy (nor probably enjoyable) experience and you’ll inevitably end up not doing the documentary the justice it deserves.

Instead, seek out people who are gifted in their respective fields and you’ll set yourself up for success. This may sound difficult – especially when on a budget – but you’ll probably find it’s easier to find folk that share your vision for a documentary than for a feature film. It’s not hard to convince people to take part in covering an issue they’re also passionate about, whereas trying to explain why your script about zombies in space is going to be the ‘next big thing’ can be an uphill struggle.

This is also one of the biggest benefits of documentary school: you’ll never be short of bright stars with which to collaborate.

3. Shoot a Film, Not a Documentary

Michael Moore is one of the most controversial documentary filmmakers of the modern age; love him or hate him, he certainly knows how to push buttons and get his documentaries seen, so his views on the craft are worthy of consideration.

Amongst many good points raised during a candid interview with Indie Wire, Moore observes that people go to see movies for the exact same reason they see documentaries: “They want the lights to go down and be taken somewhere. They don’t care whether you make them cry, whether you make them laugh, whether you even challenge them to think – but damn it, they don’t want to be lectured, they don’t want to see our invisible wagging finger popping out of the screen. They want to be entertained.”

In short, your documentary should provoke an active emotion out of the audience – whatever that may be – not just give them information…

… there are Wikipedia pages for that.

4. Exposition Bad, Bad Reenactment Worse

As you’ve probably already figured, an exposition overload rarely makes for engaging viewing. One way that documentary filmmakers try to get around this is to reenact past events using actors – surely it’s the only way to portray a real-life event when no actual footage of it exists?

Quite often, yes; but a terribly executed reconstruction scene can be more jarring to an audience than any lengthy voiceover possibly could be. Check out some great documentaries like the Thin Blue Line, Man on Wire and the recent 1971 to see how it’s done well and try to emulate their techniques, but if you don’t feel like you’re going to be able to do it effectively, it may be time to pick another tool from the toolbox.

5. Ignore the Big and the Small

Too many documentary filmmakers first starting out worry about whether or not they’re covering big enough stories. Why focus on a homicide in a rural, Midwestern town when you can expose the entire US government, right?

Wrong. A thousand other people are going to try and tell the story of the NSA, but only one is going to end up making CitizenFour. On the other hand, only one Kurt Kuenne could have created Dear Zachary.

By focusing solely on a huge story just because it’s huge, you run the risk of being totally blindsided by it and never really finding ‘your’ angle to the whole thing. But if you stick to the age-old adage ‘shoot what you know’, you’ll be able to really own the project. You’ll also find that the locality or niche-nature of the documentary won’t hamper the chance of it getting mainstream appeal in the slightest.

If you think a story is worth telling, it almost certainly is.

Just get out there and tell it well.