Nobody involved in the early stages of making a B-movie “Jaws in space” plotted Star Beast ever expected it would evolve into the billion-dollar plus Alien franchise. From the original 1979 film about a creature that lived to kill aboard a spaceship in the middle of nowhere spawned dozens of sequels, crossovers, prequels, comics, action figures, and video games.

Alien: Isolation is just the latest in the ever-expanding universe of murderous Xenomorphs and chestbursters. The next-gen video game is an ersatz sequel to the original film, boasting state of the art realistic graphics to tell the story of Ellen Ripley’s daughter, Amanda, and her search to find her mother and the doomed crew of the Nostromo, or at the very least, the truth of what happened to them.

While reviews of the gameplay have been mixed, its story and tone have been heralded as a worthy addition to the Alien Franchise. That tone has varied with every incarnation of the series and is best explored through the feature films spread across five decades of Hollywood history. And what better way to explore a film than through its director.

The Alien franchise has managed to find a wide range of talented directors at various points in their careers, though usually early—filmmakers who have added their own mark and together have woven a complex tapestry nobody reckoned could be built around something as simple as The Beast With Two Mouths.

Ridley Scott

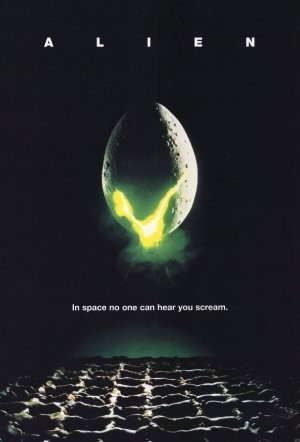

A lot of credit for the Alien franchise must go to original Alien director Ridley Scott. His patient, quiet yet epic style set up the world the franchise inhabits, and created the momentum that has since driven the series forward. By casting a seven-foot actor to inhabit the Xenomorph costume and using shadows and other filmmaking techniques to hide the Alien for most of the movie, Scott managed to create an otherworldly beast that looked too real for the special effects of the time—crucial to suspending the audience’s disbelief and scaring them out of their seats.

Scott was keen on having complex characters with backstories and motivations—something rarely seen in run-of-the-mill horror films where actors were merely fodder for their given monster. Combining this with the lived-in feel of the mining spaceship, Scott created an atmosphere not really seen in space movies before. Rather than the clean-cut scientist astronauts of 2001 and other films, the crew of the Nostromo more resembled offshore oil riggers getting paid by the hour in the Alaskan wilderness. Simply put, he made them relatable.

He also cast an unknown Sigourney Weaver in the lead role of Ellen Ripley, originally scripted as male. He not only helped Weaver launch her A-list career but created one of science-fiction’s most enduring heroines, who even thirty-five years later remains one of the few famous female leads in Hollywood genre cinema.

Alien was only Scott’s second film, but belayed the auteur’s skill with blockbuster special effects and set the tone for the rest of his career. Of all the Alien franchise’s directors, Ridley Scott is the only one to have directed more than one film. Thirty-three years after helming the original, Scott came back with the pseudo-prequel Prometheus, another slow-paced effects epic that is more concerned with our cosmic origins than with bloody deaths. While reviews of the movie were mixed, Scott proved that despite setting the tone for the franchise he could also bring it in new directions with the best of them.

James Cameron

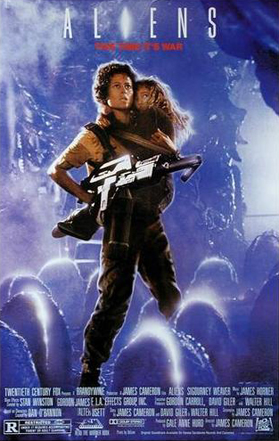

James Cameron may very well have been selected to be the director of the sequel to Alien because of his previous masterpiece, The Terminator. After all, both films centered on unstoppable killing machines following a vulnerable but strong-minded woman. Cameron, however, had other ideas, and his script for Aliens switched radically in tone from its predecessor.

Aliens is a war movie first, monster movie second, written and directed with an energy that celebrated cool guns, space tanks, and badass one-liners. Beneath its surface though was a smarter movie, the macho cheerleading a commentary on the Vietnam War, and Ripley’s character was given a depth and maternal narrative the original movie didn’t have time to establish. Aliens expanded on the first while at the same time it used its universe in entirely different ways for entirely different purposes, and cemented Cameron as an artist of the blockbuster, a future King of the World.

David Fincher

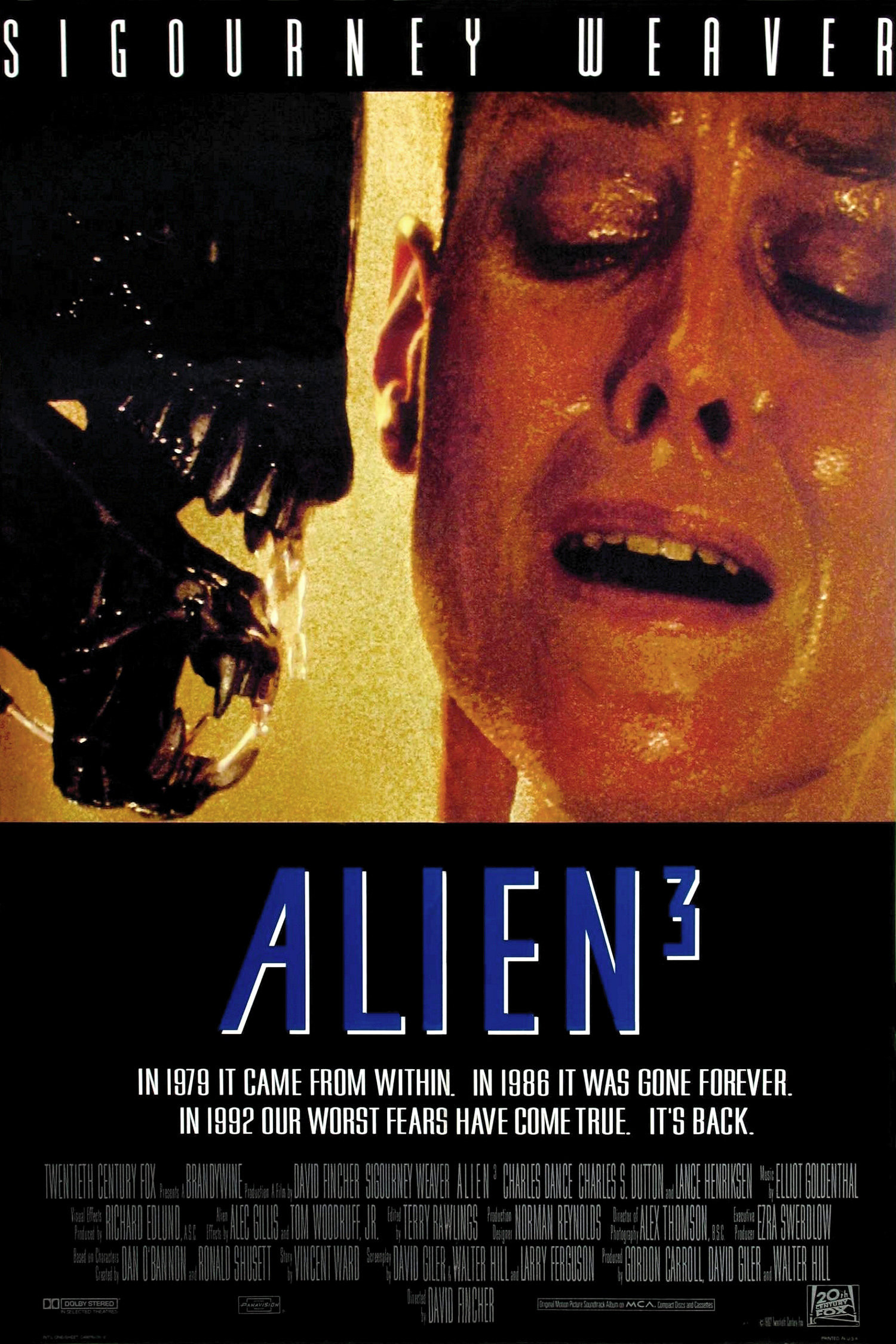

Alien 3 was David Fincher’s first film after a career of directing commercials and music videos. Fincher was reportedly plagued by constant rewrites and changes by the studio, and was so disillusioned with the experience that he almost had his name removed from the credits.

However, his stamp remains and facets of the future Oscar nominee’s style are already prevalent in the dark, gloomy sequel. Besides Fincher’s favored brown and copper tones, Alien 3 has the bleak despair and bloody gore found across his oeuvre, including his immediate follow-up, Seven. Fincher is the director who presided over the death of hero Ellen Ripley, a controversial move lambasted from fanboys and previous director James Cameron alike.

The movie has its merits though and showed the Alien franchise could do horror in various shades of gray (or bronze). It also tied Ripley’s character into a larger-than-life battle with the Xenomorphs. In the original she was a bystander, in the second she was a survivor. In the end, she would become a nemesis of an entire species, her existence and fate entwined with the Aliens. She was no longer just a genre protagonist but a bona fide science-fiction legend, her hairless visage as synonymous with the franchise as the eponymous creatures themselves.

Jean-Pierre Jeunet

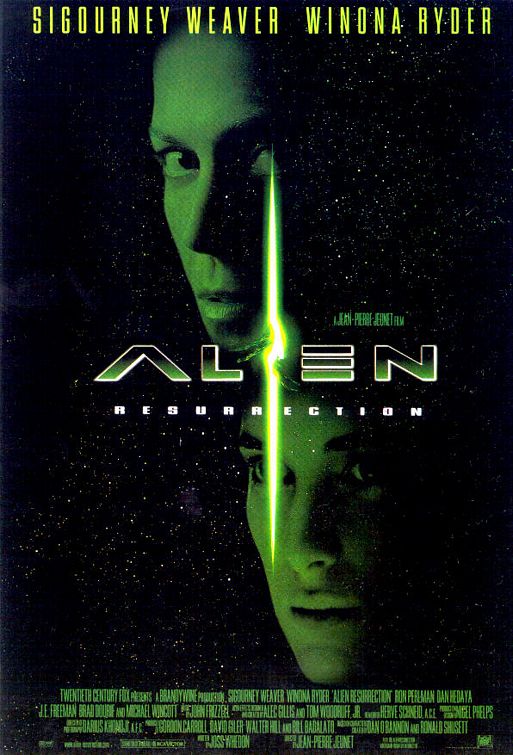

French filmmaker Jean-Pierre Jeunet had already directed the post-apocalyptic black comedy Delicatessen and dark fantasy The City of Lost Children before taking on the fourth movie in the franchise, Alien: Resurrection. His following film, Amélie, made him more of a household name, and further proved his talent with cinematography built around CGI, then coming of age.

All of these personal touches came together for an offbeat sequel that never quite felt comfortable in its own skin. Like Alien, it was set aboard a doomed spaceship, like Aliens, it had futuristic marines facing off against a multitude of Xenomorphs and their queen. Ripley’s larger-than-life status was the core of the movie, with her clone being resurrected two hundred years after Alien 3 to battle the creatures. She was surrounded by oddball characters, including Jeunet regulars Ron Perlman and Dominique Pinon. Jeunet’s fun sense of quirk best came out in the interplay between Ripley and these characters, and are arguably the strongest element of the film.

Alien: Resurrection was released in 1997, right before The Matrix and Hollywood’s CGI revolution. Jeunet’s skills behind the camera and a script by Joss Whedon struggled to do something new with the franchise, but compared to similar fare of the pre-Matrix 90s, A:R looks beautiful and is dynamically shot. At it’s worst, it’s a generic space action movie with the skin of the Alien franchise, a trait that continued as Hollywood started taking less risks and digging their franchise heels in at the turn of the century. The following two films in the series would continue that trend, and without someone as skilled as Jeunet, they would sink where Resurrection managed to at least keep its head above water.

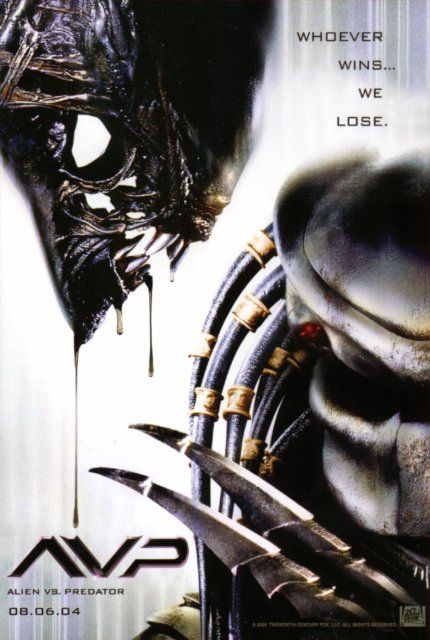

Paul W.S. Anderson

Alien vs. Predator was a departure for the series in more ways than its additional extraterrestrial species. It’s also the first film in the franchise with a PG-13 rating, limiting the film’s violence, which in capable hands is not just a tool but part of the series’ foundation.

The PG-13 is one result of Hollywood’s twenty-first century movement to bring in as many viewers as possible. With ever-expanding budgets, it’s become paramount for films to make more money, which has led to duller, more mainstream-oriented fare and a dependency on recognizable names. Aliens had been fighting Predators for over a decade in other media—it was only in the 2000s that Hollywood felt the need to combine the two trademark properties.

While both the original Alien and Predator movies were slow-burns with its monsters picking off the cast one by one, AvP is a loud action film that is more interested in hitting its plot points fast enough to keep teenagers interested than it is in developing character or creating any sort of commentary or subtext. Far enough from the original, AvP also loses itself in nostalgia by beating the audience over the head with callbacks to the previous films rather than using them to season an original take on the mythology.

Of all the directors, Paul W.S. Anderson was the most experienced when he got behind the camera, having already made blockbusters like Mortal Kombat, Event Horizon and Resident Evil. While the previous Alien films all took chances with relatively unknown auteurs, it was a sign of the times that the franchise was placed in the hands of someone more workhorse than artist.

What could have been an exciting crossover with new things to say and new ways to say it, Alien vs. Predator continued the downward slope of the franchise by being just another dumb action flick.

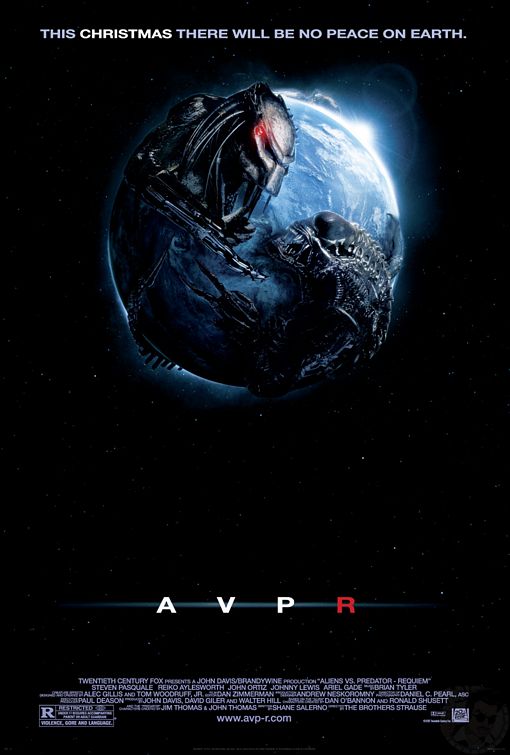

The Brothers Strause

Colin and Greg Strause were untested filmmakers with a respected expertise in special effects when they took on the follow-up crossover, Aliens vs. Predator: Requiem. The ho-hum response to the original AvP was strong enough for the studio to take a little more risk with the film, also allowing again for an R rating.

Unfortunately the Brothers Strause used the R rating for more gore, whether it be a maternity ward full of eviscerated wombs or a chestburster tearing itself out of a child’s body. This was shock value for shock value’s sake, as opposed to a genuine twist meant to disrupt the audience and change the game completely like the original chestbursting scene from Alien. The visceral violence wasn’t a product of an omnipresent despair like in Fincher’s Alien 3 but just another bullet point to check off on the Brothers’ how-to-make-a-horror-film checklist.

The result is a B-movie with slightly more character than the previous AvP but another forgettable entry for the franchise. Not as offensively bland, it isn’t impossible to sit through while watching, but as soon as it’s over you won’t remember much. That in itself may be the cardinal sin for the Alien franchise—the Xenomorphs have proven that they’re anything but forgettable.

Even their token appearance at the end of Ridley Scott’s Prometheus was treated like an event. The franchise is currently dormant, but it will only be a matter of time before studio heads find a new way to approach the series, and like a mysterious otherworldly egg, it will slowly stir and come to life and bring us a new monster. Hopefully it will be a monster worth screaming at.