Birdman winning an Academy Award for Best Picture wasn’t much of a surprise. Earlier in the ceremony, it had already picked up Oscars for Best Screenplay, Best Directing, and Best Cinematography. The Cinematography award went to the film’s director of photography, Emmanuel Lubezki, giving him a record-tying two Oscars in a row in the cinematography category. Lubezki had won the year before for the stunningly shot Gravity.

Birdman Cinematography: A Visual Symphony in Filmmaking

Like Gravity and other films Lubezki shot, including Tree of Life and Children of Men, Birdman is known for its long takes—single, seemingly unedited shots of several minutes or more in length. In fact, Lubezki and writer/director Alejandro González Iñárritu worked very hard to make Birdman seem like it was shot entirely in a single, continuous take.

This was achieved by combining several long takes and making their transitions as hidden and seamless as possible. For the most part, it was successful and is considered a major factor in Birdman’s considerable award season praise.

While the film used camera tricks and illusion to make Birdman seem like a two-hour-plus single take, it still involved several long shots that are incredibly difficult to film in a practical setting. According to Lubezki, most shots are around ten minutes in length, with the longest take around fifteen. Even a single one of these takes would be considered a daunting and possibly unnecessary task in a production.

How did the Birdman team (Birdteam?) pull this off? With lots of practice. A proxy set resembling the labyrinthine backstage hallways of the St. James Theatre—where Birdman is set—was built in Los Angeles before filming began. It was there that Iñárritu and Lubezki blocked out each shot, playing Birdman’s jazzy, drum-based score in the background to help set the tone. By plotting and practicing each long take, the filmmakers were able to figure out how and where they could hide their shot transitions, as well as get an idea of where to stage their actors and place their lights. They realized for the more difficult shots, visual effects, and special cinematography techniques would be needed to help with the transition.

Shooting and combining these takes assisted in the mobility of the Steadicam, which Lubezki employed throughout filming. The cinematographer has become well known for his intense handheld shots, and Birdman was no different. He personally operated the camera for many handheld shots and relied on veteran Steadicam operator Chris Haarhoff for Steadicam shots, working with him and directing him in real time to better capture the improvisational production of the film and respond to the actor’s movements and unpredictable natural lighting. A 2nd AC would also follow the operator for some shots to spot necessary camera moves.

The cameras used in Birdman included the Arri Alexa and, for the handheld and Steadicam shots, the Alexa plus. The Alexa M was used for some remote and extreme handheld work, using a custom-built backpack holding an external recorder, its batteries, and a wireless transmitter. The primary lenses used were Leica and Zeiss Master Primes. While many cinematographers would avoid using extremely wide lenses for close-ups, Lubezki, considered a master with wider lenses, did not hesitate to use the Zeiss Master Prime 12mm and similarly wide lenses even for tight close-ups in the claustrophobically shot film, creating many memorable and intimate images.

Camera movement wasn’t Birdman’s only technical feat. Iñárritu did not shy away from using strong colors like red, blue, and green to enhance the drama of the film. Blue and red were used in particular on stage in the play-within-the-movie. Scenes shot outside, with the theater exterior just yards away from Times Square and a memorable scene in the heart of Times Square itself meant the filmmakers had to work around New York City’s omnipresent artificial lighting.

The lighting proved particularly tricky considering the long, varied takes—without the safety net of cutting, Lubezki had to hide his lights out of frame very carefully. In typical cinematic shots, not only do cinematographers take pains to hide the physical lighting equipment and cables out of frame, but they also must maintain the angle of their source within a camera move—shadows or other lights could betray the artificial sources if a shot is not blocked and choreographed correctly. During Birdman’s long takes, with shots often showing 360-degree angles of the set, maintaining this lighting continuity was an epic struggle.

Not only did Lubezki find the right placement for his lighting equipment, he had his grip team constantly move them during the shot, with the lights dancing just out of the frame and moving along with the actors, Lubezki and the camera operator. They would move not only heavy, superhot lamps but also the gels and diffusions bouncing their light and shadows, all to maintain the illusion of a natural source within the shot. This needed to be done for every single take of nearly every single shot in Birdman.

To minimize lighting equipment and allow for what Lubezki called “a ballet” of hustling and shifting crew members, Lubezki pushed the Alexa to an ISO of 1280 with the aperture open wide. By making the camera more sensitive to light in this way, Lubezki reduced the need for larger and more elaborate lighting setups, giving the camera, actors, and crew more freedom and room to move around within each tracking shot.

Lubezki and Iñárritu also employed the use of lens flares to add visual texture to Birdman. By having lens flares on the film’s copious wide-angled close-ups, Lubezki was able to soften the image, lowering the contrast and making the actors’ more intimate scenes prettier and more emotional.

Simply put, Birdman was more than just a string of gimmicky long takes. If the Oscar for Best Cinematography was given on a purely technical level, Birdman would be more than worthy of it. If the Oscar was awarded based on artistry and how beautifully shot a film is, then Birdman would be more than worthy of it. The Oscar, however, is given based on a combination of both these qualities. Birdman was more than worthy of it.

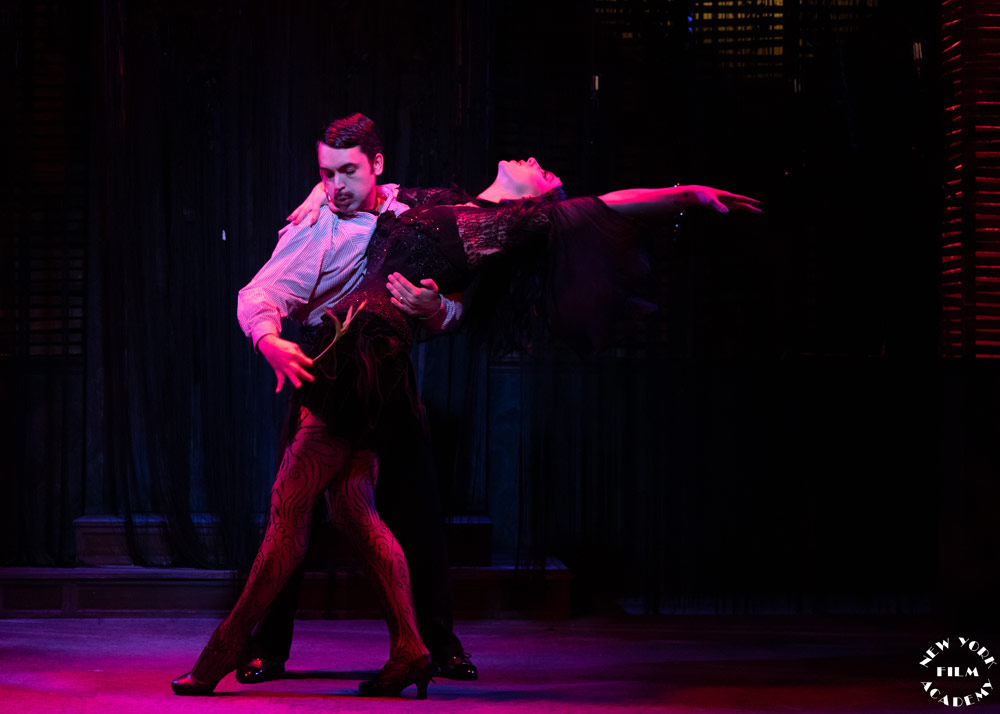

Excel in Cinematography at NYFA

In our MFA in Cinematography program, aspiring cinematographers strengthen their skills in composition, lighting, and camera movement and learn how to achieve similar cinematic techniques. To learn more about the MFA, visit the degree page.